- African-American History Month

- Presidents & Baseball

- Grounds and Garden

- Easter Egg Roll

- Christmas & Holidays

- State of the Union

|

Home >

History & Tours >

History & Tours >

Art in the White House: A Nation's Pride >

Art for the President's House

|

|

Art for the President's House — - Franklin Delano Roosevelt - The white building that stands at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in the nation's capital city is familiar to most of us, yet few people are frequent callers there. When Franklin Roosevelt said that this house is owned by all the American people, he had something else in mind. Whatever our political views,family backgrounds, or special interests, we all live there in a sense through shared history and citizenship.

To walk over the manicured grounds toward the White House entrance is to feel the significance of our nation's history. Those who do cross the threshold of the President's House renew a kinship with what must be understood as a widely extended family. Like a grand European house of three or four hundred years ago, the White House encloses both public and private rooms that serve multiple functions. Through the same hallways pass the casual vacationer, the hurried diplomatic adviser, and the current presidential family. Their common ground is the house itself and the history it represents.

First occupied in 1800, the

White House has served as the official residence of all the

Presidents of the United States except

Not surprisingly, the families of the

Members of

Abraham Lincoln's family presented portraits of both Lincoln and his

wife.

Theodore Roosevelt's family gave a black and white illustration by

Frederic Remington that features one Roosevelt's adventures.

These gifts from presidential families, however, account for

only a small number of works acquired over the years. More recently the

growth of the fine arts collection has depended heavily on the generosity of

the American public, and today the Executive Mansion houses nearly 450

examples of painting and sculpture.

A number of works by important artists--Jasper Cropsey, William Glackens,

and Maurice Prendergast among them--have been given by their descendants.

Other individuals too have become participants in the national collecting

enterprise, securing works of art for the "house owned by all the

American people." One donor, upon learning that the Executive Mansion

wanted to acquire a particular view of the Rocky Mountains by Albert

Bierstadt, purchased it, placed it on loan, and eventually gave it to the

collection. When a newspaper reported that the White House had been the

unsuccessful bidder for a genre scene by George Caleb Bingham, a

citizen of the artist's home state, Missouri, offered a contribution. He

donated a share in the river scene by Bingham that he owned, and funds

from a second donor completed the purchase. Aware of

President Jimmy Carter's admiration of William M. Harnett's

Cincinnati Enquirer (at left, below), on loan to the White House,

a donor bought it for the collection.

In 1976 two sisters from Kentucky presented Fredrick Remington's

Bronco Buster, believing its display in the White House would

"inspire a feeling of strength and determination of the American spirit"

characteristic of their father, the previous owner. The formation of

the White House collection has involved not only

Presidents

and

First Ladies

but also politicians, curators, collectors,

librarians, interior decorators, and others, working in concert and

in conflict over some 200 years. Yet the

collection remains unified by three basic concerns: art--chiefly American

art--as historical document, as decoration, and as vehicle for

celebrating American values and achievements. All three themes appear

again and again in the subject matter of the art, in the intentions of

its creators, in the taste of its donors, and in the

eyes of the beholders. These threads have been constantly

interwoven throughout the past two centuries, but the historical has

been the strongest and the most evident collecting criterion.

For much of the time, subject matter took precedence over the

artist's reputation or the work's quality of execution. Portraits of

early Presidents were copied during the 19th century to provide

the White House with suitable likenesses. This

documentary emphasis resulted in paintings that vary widely in quality and

often lack the vitality and character of the life portraits they

replicated or interpreted.

By the 1880s Presidents and First Ladies began commissioning grander

portraits from nationally known and even internationally famous artists.

Perhaps our turn-of-the-century leaders wished to have more of a hand

in how they were remembered, a change that itself indicates the rise of art

consciousness. As the collections policy of

the White House became more clearly articulated and as the field of

American art matured as well, acquisitions criteria were

greatly expanded to give artistic considerations more

weight, balancing the documentary excesses of previous generations. Yet the

acquisition of life portraits of the Presidents and First Ladies

consistently remained the first priority for the

collection.

Hanging in the

East Room, the most prominent ceremonial space in the White House,

the Father of the Country presides over bill signing ceremonies, official

entertainments, and press conferences.

That the head replicated an earlier painting by Stuart, while the hands

were taken from studies of a live model, explains the somewhat

disembodied quality of Andrews' grand manner portrait. After the exposition

the canvas was displayed at the White House, where another journalist

noted that the dress seen on Martha Washington in the painting

was designed by the Parisian couturier Worth- and made for a New York

socialite to wear during the nation's Centennial, a century after

Martha's time. Nonetheless, the reporter found the portrait "without a

doubt the central object of attention at the

White House."

Today the White House collection includes canvases of

First Ladies far surpassing Andrews' work in artistic quality, but

the monumental portrait still occupies the place of honor in the East

Room. The figure rests her hand upon a fancy chair that was not

produced until years after Martha Washington's death. That the chair is

incongruous, or that the dress was designed in 1876 rather than

1776, is not particularly disturbing to most visitors who

encounter Mrs. Washington's regal image in the

East Room. She is not there as a great portrait, but as an important

presence.

Lucy

Hayes, wife of then

President Rutherford B. Hayes, lobbied for this purchase as a

companion piece to the much older image of George Washington.

Eventually Congress purchased Andrews' canvas for

the not inconsiderable sum of $3,000.

Years later,

Theodore Roosevelt's wife Edith, established a

First Ladies portrait gallery in the Ground Floor Corridor; this

image remained enshrined on the State Floor. "There is just one likeness

of a woman which has not been consigned to the ill lighted basement gallery,"

commented a writer for Munsey's Magazine.

This is the portrait of Mrs. Washington who was never mistress of

the White House--by Andrews, which has the honor of hanging... near the Stuart portrait of her illustrious

husband.

More than three-quarters of a century stretches between the acquisition

of portraits of George and Martha Washington. During that period, and

especially from 1800 to 1850, the Executive Mansion experienced a

succession of expensive redecorations but acquired little art through

gifts or purchases. During

Andrew Jackson's two terms alone, Congress appropriated nearly $50,000,

an enormous sum, for refurbishing the house and adding the North

Portico; none of the money seems to have been used to commission or

purchase artwork. Certainly there was no dearth of available painters,

for artists such as Trumbull, John Vanderlyn, and Samuel F. B. were at

work on important portraits and historical paintings

commissioned for other locations, notably the United States Capitol.

But at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue presidential images were as transient

decor. The much admired furnishings of one administration quickly became the

castoffs of the next, and Presidents usually retained their personal

commissioned portraits upon leaving the White House.

In 1826 Trumbull, desiring a commission to paint historical pictures for the

Capitol, begged for the "patronage of government." He observed that such

support "the fine arts may be stimulated and encouraged, the national

edifices decorated, authentic monuments of national

history preserved, elegant and attractive

rewards bestowed on the meritorious servants of the public, and

the national glory essentially advanced."

Ultimately, this inattention may have been a result of the

way the

White House itself was viewed--as a home, not as a public building.

Since the early 19th century the Executive Mansion has mirrored

democratic attitudes toward domestic fashion and decoration, making a

self-conscious departure from the grander tradition of the great state

residences of the Old World.

George P. A. Healy arrived on the Washington scene in the midst of this

new period of activity when Congress commissioned him in 1857 to paint

a series of presidential portraits. The series was the first effort to

obtain for the White House a visual record of its prior inhabitants.

Healy had just returned from Paris, where he had achieved a

significant reputation and won the patronage of Louis Philippe,

Citizen King of the French, and Lewis Cass, American minister to France.

A sophisticated artist accustomed to mingling with politicians,

diplomats, and royalty, Healy had already painted

such American notables as Andrew

Jackson, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. In 1842 he had worked in

the White House, making a copy of Stuart's

Washington for Louis Philippe, and he had already met and even

painted some former Presidents whose likenesses were still needed for the

White House. In just a few years Healy completed portraits of

John Quincy Adams,

Martin Van Buren,

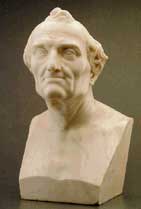

John Tyler (at left)

The series was an imposing one. Healy's Presidents were portrayed in the

grand manner: full length, standing or seated, surrounded by opulent

accessories, their gestures commanding and their demeanor grave.

The artist's work was interrupted by the Civil War, however, and his

unframed paintings were temporarily relegated to the attic.

Art for the President's House — An Historical Perspective

|

The great-great grandson of

The great-great grandson of

A full-length

portrait of

A full-length

portrait of