- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Budget Management

- Defense

- Economy

- Education

- Energy

- Environment

- Global Diplomacy

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- International Trade

- Iraq

- Judicial Nominations

- Middle East

- National Security

- Veterans

|

Home >

News & Policies >

October 2006

|

For Immediate Release

Office of the Press Secretary

October 5, 2006

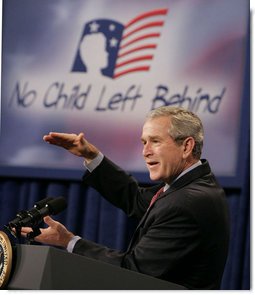

President Bush Discusses No Child Left Behind

Woodridge Elementary and Middle Campus

Washington, D.C.

![]() Fact Sheet: The No Child Left Behind Act: Challenging Students Through High Expectations

Fact Sheet: The No Child Left Behind Act: Challenging Students Through High Expectations

![]() In Focus: Education

In Focus: Education

11:02 A.M. EDT

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you all. Thank you for the warm welcome. Thank you for inviting Madam Secretary and me to your school. It's nice to be introduced by somebody with a Texas accent. (Laughter.) She's a good buddy, and she is doing a fine job as the Secretary of Education. So, Margaret, thank you very much for your service.

I'm glad to be at Woodridge, as well. I'm here because this is one of

America's fine public charter schools. I'm here to remind people that

charter schools work, and they can make a difference in the lives of our

children. So I want to thank you for letting me come. I want to thank the

teachers and the administrators and the principals -- and the principal,

for setting high expectations. I know that sounds simple, but you know

what happens when you set low expectations? You get low results. And so a

center of excellence is always a place of learning where people believe the

best. And I want to thank the folks here for setting high expectations. I

want to thank you for achieving results.

I'm glad to be at Woodridge, as well. I'm here because this is one of

America's fine public charter schools. I'm here to remind people that

charter schools work, and they can make a difference in the lives of our

children. So I want to thank you for letting me come. I want to thank the

teachers and the administrators and the principals -- and the principal,

for setting high expectations. I know that sounds simple, but you know

what happens when you set low expectations? You get low results. And so a

center of excellence is always a place of learning where people believe the

best. And I want to thank the folks here for setting high expectations. I

want to thank you for achieving results.

I applaud the parents of the students who are here for being -- and I applaud you for being involved in the life of your children, particularly when it comes to one of the most important aspects of their development, and that is school. And I want to thank the students for letting me come, too.

I want to thank Mary, the principal. You know, one of the things I have found, and I've spent a lot of time in schoolhouses as a result of being the governor and the President is that a good school always has a good principal. (Applause.) And Mary Dunnock must be a good principal, because this is a good school. And I applaud you for being an educational entrepreneur. An educational entrepreneur is somebody who is willing to challenge failure and mediocrity if she finds it, because failure and mediocrity are unacceptable in any classroom anywhere in the United States. (Applause.)

I thank Donald Hense for joining us, Founder and Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Friendship Public Charter School. (Applause.) Mr. Hense told me he had the opportunity of meeting my mother one time, and I said to him, well, you met the A-team then -- (laughter) -- now you met the B-team. (Laughter.) But thank you for your leadership. I welcome the members of the Friendship Public Charter School Board. Thank you for coming.

Being on a school board is difficult work, I know. Being on a school board that challenges the status quo is important work, and I thank you for that. It means a difference -- I was in Lyle Brown's class. Lyle is not here. He's still teaching. But one of the things I saw was a teacher who loves being a teacher. (Applause.) And I applaud the teachers in this school and teachers all around the country who are -- who are adding to the great future of our country.

I was in Max Brooks' class. He's not here either, but he is the

facilitator in what's called a SmartLab. They didn't have SmartLabs when I

was going to elementary or junior high school. They've got one here. And

it's an innovative program that teaches people practical skills. You know,

one of the interesting questions I like to ask to students when I go into

the classroom is, how many of you are going to go to college? You'll be

pleased -- there you go -- you'll be pleased to hear that hands went up.

(Applause.)

I was in Max Brooks' class. He's not here either, but he is the

facilitator in what's called a SmartLab. They didn't have SmartLabs when I

was going to elementary or junior high school. They've got one here. And

it's an innovative program that teaches people practical skills. You know,

one of the interesting questions I like to ask to students when I go into

the classroom is, how many of you are going to go to college? You'll be

pleased -- there you go -- you'll be pleased to hear that hands went up.

(Applause.)

See, that's a good sign when the principal and students and parents have encouraged our children to set a goal. Going to college is an important goal for the future of the United States of America, and I'm please to report that when I asked that question in both classrooms I was invited to go to, there was unanimity.

The students have set a goal to go to college, and I reminded them that now is the time to work hard so you get to go, like take advantage of the SmartLab, read more than you watch TV, practice your math and science. I want to applaud you, Madam Principal, for encouraging our students to aim high, and I thank the teachers for helping them achieve those dreams.

In recent days, we have seen some sad and shocking violence in our schools across America. Yesterday, I was in Colorado, which is one of the states that had received this sad and shocking news firsthand.

Next week, Secretary Spellings and Attorney General Al Gonzales are going to host a conference here in Washington, D.C., and it's an important conference. We're going to bring together teachers, and parents, and administrators and law-enforcement officials, and other experts to discuss ways to help our schools protect the children. See, it is paramount that the federal government work with the state government and local governments to make it clear that our schools are places of learning, not places where there will be violence. And so, Margaret, I want to thank you for that initiative, and I'm looking forward to hearing the results of the important discussions.

I'm here today to talk about the No Child Left Behind Act. It's a -- this act is an important way to make sure America remains competitive in the 21st century. We're living in a global world. See, the education system in America must compete with education systems in China and India. If we fail to give our students the skills necessary to compete in the world of the 21st century, the jobs will go elsewhere. That's just a fact of life. It's the reality of the world in which we live. And therefore, now is the time for the United States of America to give our children the skills so that the jobs will stay here.

Oh, there will be jobs -- don't get me wrong. But I'm talking about the

high-paying jobs, the quality jobs, the jobs that will be helping to lead

the world in the 21st century. And there's no doubt in my mind we can

achieve that objective. And the No Child Left Behind Act was all part of

making sure that we get it right in the schools. So when I came here to

Washington I made a focused effort to work with Democrats and Republicans

to pass this important law. And the theory behind the law is

straightforward: We'll spend more money on education, but in return, we

want to see results.

Oh, there will be jobs -- don't get me wrong. But I'm talking about the

high-paying jobs, the quality jobs, the jobs that will be helping to lead

the world in the 21st century. And there's no doubt in my mind we can

achieve that objective. And the No Child Left Behind Act was all part of

making sure that we get it right in the schools. So when I came here to

Washington I made a focused effort to work with Democrats and Republicans

to pass this important law. And the theory behind the law is

straightforward: We'll spend more money on education, but in return, we

want to see results.

Oh, I know that may be too much to ask for some. It's not too much for this school. As a matter of fact, I get a little nervous when I hear people say, well, I don't want to be measured. My attitude is, what are you trying to hide? How can you solve a problem until you measure the problem? How can you make sure a child is achieving what we all want if you don't measure early to determine whether or not the skills are being imparted?

And so the No Child Left Behind says, look, we trust the local folks. I don't want Washington, D.C. running the schools. That's up to the people in the states and the local community. I've been a strong believer in local control of schools. But I also believe it makes sense to ask the question, whether or not a child can read, write, and add and subtract. I don't think it's too much to ask. I know it's an important question if we expect our children to have the schools [sic] necessary to compete in the 21st century. I know the kids don't like tests, and I didn't like it either, to be honest with you. You hear people say, well, we're testing too much. No, we're just trying to figure out whether or not people have got the skills necessary to succeed.

You know, I remember the debates when I was the governor of Texas and Margaret and I were working on accountability systems. I remember somebody standing up and saying, it is racist to test. I said, uh-uh, it is racist not to test, because there are too many children being shuffled through our schools without understanding whether or not they can read and write and add and subtract. I think it's important to hold people to account now to make sure the education system functions for all. And that's the spirit of No Child Left Behind.

By measuring, it helps us determine whether or not a curricula works. Is the reading curriculum you're using working? That's a fundamental question a parent ought to ask, or a principal ought to ask, or a teacher ought to ask. The best way to find out is to measure to determine whether or not a child can read at grade level. And that helps you determine whether or not your curriculum are working.

One of the things that I think is most important about the No Child Left Behind Act is that when you measure, particularly in the early grades, it enables you to address an individual's problem today, rather than try to wait until tomorrow. My attitude is, is that measuring early enables a school to correct problems early.

See, let's be frank about it. We had a system that just shuffled kids through grade after grade. I know some say that wasn't the case, but it was -- let me just say, my state, the place I was familiar with. It's so much easier, when you think about it, just to say, okay, if you're such and such a grade, you're supposed -- age, you're supposed to be in this grade, and just shuffle them through. And guess who got shuffled through? Inner-city kids, the hard to educate. It made it easy just to say, oh, gosh, let's just -- you know, let's don't worry about whether or not you've got the skills. Let's just put you here because that's where you belong. That's unfair to parents. That's unfair to the children. And the No Child Left Behind Act demands result for every child, for the good of the United States of America. (Applause.)

There's an achievement gap in America that's not good for the future of this country. Some kids can read at grade level and some can't. And that's unsatisfactory. I know it's unsatisfactory for the educators who are here. It's unsatisfactory if you're a parent, and it's unsatisfactory for the President.

You can't have a hopeful America if certain kids can read at grade level and others can't, and we don't address the problem. I'm proud to report the achievement gap between white kids and minority students is closing, for the good of the United States.

How do I know? Because we measure. In reading, nine-year-olds have made larger gains in the past five years than at any point in the previous 28 years. That's positive news. In math, nine-year-olds and 13-year-olds earned the highest scores in the history of the test. In reading and math, African American and Hispanic students are scoring higher, and the achievement gap is closing.

Oh, I know people say we test too much, but how can you solve a problem until you measure? And how can you hold people to account when there's an achievement gap that is not right for America, unless you measure? Measuring is the gateway to success.

Woodridge Elementary School gets measured. The accountability system helped your school identify struggling students and enabled them to get the help they need early. I appreciate the fact that you have intervention sessions with teacher assistance. In other words, we identify a particular child's problems, and then this school intervenes. You have specialized learning projects, extra tutoring.

Each child matters. Every child has potential. All hands went up and said, I want to go to college. And this school recognizes that some students need a little extra help early to make sure they can realize those dreams. That's what measuring helps you to do.

Woodridge has met the standards for three years in a row. You've put in a lot of hard work and you have the results to show for it, and I thank you for your contribution to the future of this country. (Applause.)

If you don't make progress, you get extra help. One of the most important initiatives is the Supplemental Service Initiative. This initiative says that when we find a child that needs help, that child gets extra help. In other words, if a child is falling behind. Remember, I keep talking about individual children. It used to be when they measured, they just measured everybody, you know. And now we're forcing them to disaggregate results. That's a fancy word for saying, just split individuals out so we know.

And when we find a child that needs extra help, there's money to do so. And there are options for parents, which is an important part of making sure there's parental involvement, and making sure -- an important part of making sure the strategy works.

A parent can enroll their child in a free intensive tutoring program. There's money for that. If your child is not up to grade level early on, there's extra help available for each family to do so. Parents can transfer their child to a better public school if that school refuses to change. In other words, at some point in time, there's got to be some accountability. It's one thing to be talking the talk about educational excellence, but pretty soon, if nothing happens, a parent ought to be allowed to walk. And that means to another public school, just like Woodridge, see.

If you're in a neighborhood and one school won't teach and change, and another school will, I think it makes sense for a parent to have the option, with space available, to be able to say, I've had it. I'm tired of my child being trapped in a failed school; I'm owed better as a parent and a property taxpayer than failure, therefore, I'd like to move my child to another school.

And that's what's happened to some of the students right here. Asia Goode -- where's Asia? Oh, thank you for coming, Asia. Can I quote you? Thank you. I was going to quote you anyway. (Laughter.) Asia first came to Woodridge; she was reading well below grade level. How do we know? Because she measured. Her teachers stayed after school to tutor her, and she caught up. Somebody said, it is my job to make sure this individual is not left behind, and not just shuffled through. And I thank that teacher for doing that.

Even after Asia reached grade level -- in other words, we measure to determine whether a child can read at grade level -- the teacher said, wait a minute, grade level is not good enough for you, Asia. I started off my speech by saying we're setting high standards. That's how you help somebody achieve educational excellence. Asia is now an honors student. She loves reading and she sings in the school choir. And I congratulate her parent and the teachers and Asia for setting high standards and working hard to achieve those standards. (Applause.)

Washington, D.C. has a really innovative and interesting program that I strongly support, as did your Mayor, Mayor Williams. Oh, I know it's controversial for some, but it rests on the premise that a parent ought to have different options if a child is trapped in a school that won't teach and won't change. I happen to think that is a good, solid principle on which to operate -- that the parent is the primary teacher of a child, and the parent ought to have different options for his or her child.

And so the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program was enacted. And it wasn't easy to enact it. There are some who are willing to defend the status quo at all costs. That's okay, that's generally what happens sometimes in the political arena. But this is a program that enables a parent to transfer his or her child to a private or religious school if the parent feels like the current school isn't working. This program is aimed particularly at low-income students.

Let's be frank about it; upper-income families have got school choice. They can afford it. Low-income families don't. This program enables low-income families to say, I'm sick and tired of my child not receiving a quality education. Eighteen hundred low-income students have used these scholarships. One of them is Carlos Battle. Carlos isn't here, but I thought his quote might interest -- he was in a school and he transferred to Assumption Catholic School two years ago. In other words, his parents -- family qualified, received a scholarship, and off he went.

After transferring, he made the honor roll. He became the class president. He led the basketball team to its first championship. He said this, "There is no limit to what I can do. And that not only makes me happier, but my mom can't seem to stop smiling." It is really important that as we think about how to make sure every child gets a good education, that we not only measure, but we say that if things don't change, parents ought to have different options.

The No Child Left Behind Act is good progress, but we've got a lot of work to do, and it starts with making sure that here in Washington we don't soften our desire to hold schools accountable. I'll tell you, look, there's a lot of pressure, and I'm sure the congressmen and senators feel that pressure. They feel the pressure because people say, look, we're tired of measuring. They feel the pressure because, you know, we're just teaching the test. I mean, there's every excuse in the book.

But as we come time to reauthorize the No Child Left Behind Act, my attitude is, instead of softening No Child Left Behind, we need to strengthen it. The law is working. It makes sense. We must hold schools account -- to account if we expect our children to be able to realize dreams. And if we want America to remain competitive, we must have high standards.

You know, there's a -- kind of a mind-set at times, a culture that says, well, you know, maybe certain kids can't learn, and therefore, let's don't have high standards. I reject that notion. I strongly believe every child has got the capacity. And all of us must demand that the high standards be set and met. And so one of the top priorities next year for me will be the reauthorization and the strengthening of the No Child Left Behind Act. (Applause.)

Here are some ways to improve the law: In order for every child to get up to grade level, there must be a quality teacher in every classroom. And one way to help the law is to help our teachers in an innovative way. We created what's called the Teacher Incentive Fund. It allows states and local districts to reward teachers who demonstrate strong results for their students. It's an interesting concept, isn't it? In other words, if your measurement system shows that you're providing excellence for your children, it seems to make sense that there ought to be a little extra incentive to do so through the bonus program, not run by the federal government -- funded by the federal government, administered by states and local governments.

I think it's very important to encourage our good teachers to teach in some of the toughest school districts. You know, when you find a good teacher, a good high-quality teacher in a -- for example, an inner-city district needs help, or a rural district needs help, there ought to be a bonus system available, an incentive program to say to a teacher, thanks; thanks for heading into some of the -- you know, an area that is -- that needs help, and here's a little incentive to do so. So there's some ideas that Congress can work on in order to provide incentives for our teachers.

I believe we ought to encourage math and science professionals to bring their expertise into the classrooms. I remember going to a school here in Maryland recently. Margaret and I went over there, and I met a guy who worked at NASA. And do you know what he was doing? He was in the classrooms basically saying to the 7th and 8th graders, science is cool; take it seriously.

You know, it's important that you learn the skills necessarily to be good scientists because it's important for the United States of America that we've got young scientists. And by the way, every neighborhood in America can produce young scientists. And therefore encouraging these professionals in the classroom as adjunct teachers makes a lot of sense, and Congress ought to fund that program.

We've got to improve options. One of the problems we have in the Public School Choice program is parents aren't getting information on a timely basis. So in other words, you got your kid going to a school, the school's accountability system says, wait a minute, you're not doing as well as you should. And the parent gets notified after the next school year begins. That doesn't help.

It kind of looks like people are afraid to put out results for some reason. And so we'll work with Congress to clarify the law and to strengthen the law to make sure our parents get timely information and useful information so that they can take advantage of the No Child Left Behind Act's law that provides flexibility and transferability.

We're going to work with school districts to help more students take advantage of free, intensive tutoring. You'd be amazed at the number of districts that don't use this extra tutoring. They don't take advantage of the extra money to help an individual child. Oh, they'll figure out ways to spend it, don't get me wrong. But the money is aimed for helping an individual succeed, and it's the cumulative effect of bringing these students up to grade level that will enable us all to say we're more competitive for the future.

I believe in opportunity scholarships. I believe that the program here in Washington, D.C. ought to be replicated around the country. I call on Congress to create such a program for 28,000 low-income children as a beginning step to help parents challenge failure.

We've got to do something about our high schools, by the way. I think there needs to be strong accountability in America's high schools. There's strong accountability right here at Woodridge. It seems like it makes sense, if it's working, to extend that concept to our high schools.

One out of every four 9th graders in America does not graduate from high school on time. That's unacceptable. If we want to be competitive, we better make sure that the skills that are now being imparted at elementary school and junior high carry on through high school. We don't want the good work here at Woodridge to be lost because there's -- because some say, well, I don't need to get out of high school, or the accountability systems in high school don't measure up. And so what I want to do is I want to have the same sense of accountability in our high schools that we have in our junior high and elementary schools -- not to increase the testing burden, but to help us understand whether or not we are achieving our national objective, which is giving our kids the skills necessary to be competitive.

And so I think we need to fund testing early in the high-school systems, and to help students fix problems like we're doing in elementary school and high schools [sic]. I proposed a billion-and-a-half dollar initiative; Congress needs to fund it.

I've also proposed a program to train 70,000 teachers over five years to lead Advanced Placement classes in our high schools. Advanced Placement works. It is a -- it is an excellent program that helps our high schools set high standards. And it calls -- it challenges our students to achieve great things by raising the standards.

Many of you know about AP. It needs to be spread all throughout America. And step one is to make sure our teachers have the skills necessary to teach it. And step two is to help states develop programs that will help parents pay for the AP test. What we don't want is a child taking an AP class and having mom or dad say, it's too expensive to take the test. You pass an AP test, you're on your way. If you've got the skills necessary to pass an AP test, it means the education system has done its job, and our country is better off.

And so here are some ideas for the Congress and the administration to work on as we think about how to reauthorize the No Child Left Behind Act. I strongly believe this piece of legislation is working. I know it is necessary to have this kind of rigor in our school systems to say, we have done our job and given our kids the skills necessary to succeed. And I want to thank you all for serving as a great example. Thank you for inviting me. Again, I thank the teachers for teaching, and the parents for loving, and the students for reading.

God bless. (Applause.)

END 11:32 A.M. EDT