- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Budget Management

- Defense

- Economy

- Education

- Energy

- Environment

- Global Diplomacy

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- International Trade

- Iraq

- Judicial Nominations

- Middle East

- National Security

- Veterans

|

Home >

News & Policies >

July 2001

|

For Immediate Release

Office of the Press Secretary

July 16, 2001

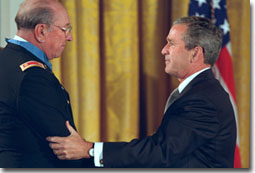

President Presents Medal of Honor to Captain Ed W. Freeman

Remarks by the President at Presentation of the Medal of Honor to Captain Ed W. Freeman

The East Room

![]() Listen to the President's Remarks

Listen to the President's Remarks

THE PRESIDENT: Please be seated. Good morning, and welcome to the White House. Today, for the first time, I will present the Medal of Honor. It's a unique privilege to present the nation's highest military distinction to Ed Freeman, of Boise, Idaho. This moment is well-deserved and it's been long in coming.

Our White House military unit is accustomed to a lot of great events, but I can assure you they started this day with a great sense of anticipation. After all, they know how rare this kind of gathering is and what it means -- to be in the presence of one who has won the Medal of Honor is a privilege; to be in the room with a group of over 50 is a moment none of us will ever forget. We're in the presence of more than 50 of the bravest men who have ever worn the uniform. And I want to welcome you all to the White House. (Applause.)

It's an honor, as well, to welcome Barbara -- a name I kind of like -- (laughter) -- Ed's wife, along with his family members and members of his unit from Vietnam. As well, I want to welcome the Vice President, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, the Chief of the Joint Chiefs, as well as members of the Joint Chiefs. I want to welcome Senator McCain. I want to welcome Senator Craig, Congressman Otter and Congressman Simpson from the delegation of Idaho. I want to welcome you all.

It was in this house in this office upstairs that Abraham Lincoln signed into law the bills establishing the Medal of Honor. By a custom that began with Theodore Roosevelt, the Medal of Honor is to be presented by the President. That duty came to Harry S. Truman more than 70 times. He often said that he'd rather wear the medal than to be the Commander in Chief. Some of you might have heard him say that. (Laughter.) Perhaps you were also here on May 2, 1963, when John F. Kennedy welcomed 240 recipients of the Medal of Honor.

By all rights, another President from Texas should have had the honor of conferring this medal. It was in the second year of Lyndon Johnson's presidency that Army Captain Ed Freeman did something that the men of the 7th Calvary have never forgotten. Years pass, even decades, but the memory of what happened on November 14, 1965 has always stayed with them.

For his actions that day, Captain Freeman was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. But the men who were there, including the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Bruce Crandall, felt a still a higher honor was called for. Through the unremitting efforts of Lieutenant Colonel Crandall and many others, and the persuasive weight from Senator John McCain, the story now comes to its rightful conclusion.

That story began with the battalion surrounded by the enemy, in one of Vietnam's fiercest battles. The survivors remember the desperate fear of almost certain death. They remember gunfire that one witness described as the most intense he had ever seen. And they remember the sight of an unarmed helicopter coming to their aid.

The man at the controls flew through the gunfire not once, not 10 times, but at least 21 times. That single helicopter brought the water, ammunition and supplies that saved many lives on the ground. And the same pilot flew more than 70 wounded soldiers to safety.

In a moment we will hear the full citation, in all its heroic detail. General Eisenhower once observed that when you hear a Medal of Honor citation, you practically assume that the man in question didn't make it out alive. In fact, about one in six never did. And the other five, men just like you all here, probably didn't expect to.

Citations are also written in the most simple of language, needing no embellishment, or techniques of rhetoric. They record places and names and events that describe themselves. The medal itself bears only one word, and needs only one: valor.

As a boy of 13, Ed Freeman saw thousands of men on maneuvers pass by his home in Mississippi. He decided then and there that he would be a soldier. A lifetime later, the Congress has now decided that he's even more than a soldier, because he did more than his duty. He served his country and his comrades to the fullest, rising above and beyond anything the Army or the nation could have ever asked.

It's been some years now since he left the service and was last saluted. But from this day, wherever he goes, by military tradition, Ed Freeman will merit a salute from any enlisted personnel or officer of rank.

Commander Seavers, I now ask you to read this citation of the newest member of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society. And it will be my honor to give him his first salute.

(The citation is read.)

(The Medal of Honor is presented to Captain Ed W. Freeman.) (Applause.)

THE PRESIDENT: We'll see you for a reception. Thank you all for coming.

END 9:51 A.M. EDT