|

Home >

News & Policies >

October 2007

|

|

For Immediate Release

Office of the First Lady

October 16, 2007

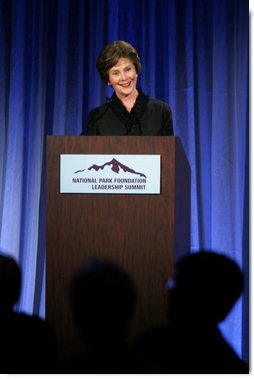

Mrs. Bush’s Remarks at the National Park Foundation's Inaugural Founders Award Dinner

Four Seasons Hotel

Austin, Texas

7:42 P.M. CDT

MRS. BUSH: Thank you, David, for that very kind introduction, and thank you for the extraordinary service you and your family have given to our national parks.

I want to say a special welcome to Luci Baines Johnson and members of the Johnson family that are here with us tonight. Governor Linda Lingle from Hawaii is here as well. Secretary Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary of the Interior; Mayor Will Wynn of Austin is with us; Vin Cipolla, the President and CEO of the National Park Foundation; Regan Gammon, the Vice Chair of the National Park Foundation -- and all the National Park Foundation board members who have joined us.

David talked about his mother and his uncle that he missed. We

also miss Lady Bird. We wish she were with us tonight. I think she did

know about this symposium, and we wish really so much that we could hear

her voice again.

David talked about his mother and his uncle that he missed. We

also miss Lady Bird. We wish she were with us tonight. I think she did

know about this symposium, and we wish really so much that we could hear

her voice again.

Thank you to everyone for your welcome home to Texas. Thank you to the National Park Foundation for presenting the first Founders Award to a legendary champion of our parks: Lady Bird Johnson.

I've always admired Lady Bird Johnson -- especially for her dedication to our natural environment. As a lonely little girl in Karnack, Lady Bird found her solace and companionship in the outdoors. "I grew up listening to the wind in the pine trees of the East Texas woods," she once said. Later, as a young woman, Lady Bird took a scouting trip to Austin on a chartered flight. She made the decision to go to school here when she looked out of her plane window, and saw a magnificent field of bluebonnets in full bloom. "It was as though the gates of the world flung open for me," she said. "I felt in love with life itself."

Mrs. Johnson carried that early love of nature and life with her all the way to the White House -- where it became a gift she shared with our entire nation. Just as a well-tended yard reflects the pride of a homeowner, Lady Bird believed that a well-cared-for landscape reflects the pride and self-respect of a nation. As her husband set about building a Great Society, Lady Bird Johnson knew America needed beautiful cities and countryside to match.

Mrs. Johnson reshaped the role of the First Lady -- and of women, for that matter -- as she pursued her dream of "beautification." She met with Cabinet officials -- including Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall -- to discuss how our government could preserve, and I quote, "the wilderness, the national parks, the shrines, the jewels of America."

She started with her own backyard, launching a major beautification

campaign in Washington, D.C. -- home to many of our most treasured

national parks and monuments. Through her Committee for a More

Beautiful Capital, Lady Bird brought together representatives from the

National Park Service and local government, architect Nathaniel Owings,

and philanthropists like Laurance Rockefeller to reverse urban decay --

and, Lady Bird hoped, to restore Washington's community pride. The

Committee's gatherings at the White House were so lively, President

Johnson once complained that their meeting woke him from an afternoon

nap. (Laughter.)

She started with her own backyard, launching a major beautification

campaign in Washington, D.C. -- home to many of our most treasured

national parks and monuments. Through her Committee for a More

Beautiful Capital, Lady Bird brought together representatives from the

National Park Service and local government, architect Nathaniel Owings,

and philanthropists like Laurance Rockefeller to reverse urban decay --

and, Lady Bird hoped, to restore Washington's community pride. The

Committee's gatherings at the White House were so lively, President

Johnson once complained that their meeting woke him from an afternoon

nap. (Laughter.)

Committee member Mary Lasker once made this observation: "Flowers in a city are like lipstick on a woman. You have to have some color." (Laughter.) Every spring when Washingtonians delight in the blossoms, they have Lady Bird's Committee to thank. Throughout the city -- including its national parks -- they planted 2 million daffodil bulbs. Japan sent 4,000 more cherry trees. Mrs. Lasker contributed 9,000 azalea bushes. In 1965, the town of Norfolk sent 500 more -- because, as Lady Bird wrote in her diary, "Luci is their azalea queen this year." (Laughter.)

The Committee cleaned up national monuments and landscaped the National Mall. But Mrs. Johnson firmly believed that everyone should contribute to and benefit from our country's natural beauty.

When Laurance Rockefeller gave the Committee its largest single gift, much of the $100,000 went to Washington's low-income Watts Branch neighborhood. Mrs. Johnson toured housing projects, and her Committee funded Project Pride, which cleared out and painted old homes in run-down D.C. neighborhoods.

At the height of the Civil Rights Era, the First Lady received a letter from an African-American boy named John Hatcher. He wrote, "I'd love for my yard to look more beautiful. If you'd please send me azaleas, I'll plant them. Then you wouldn't have to come all the way out to 50t Street to plant them for me." (Laughter.) Mrs. Johnson wrote John back, encouraging him to keep his neighborhood and school clean, and to plant more flowers. And soon after, an azalea bush was delivered to John's home.

Of course, Lady Bird's Washington days began long before she moved into the White House. During her husband's time in Congress, she drove back and forth between D.C. and Texas. From her travels, Lady Bird knew that many roadsides were an unsightly mess of junkyards and billboards. So in 1965, she expanded her beautification efforts beyond Washington, pushing for scenic highways across America.

Again, Mrs. Johnson turned to private citizens, building on the work of garden clubs and roadside councils. As President Johnson developed legislation requiring states to control billboards and junkyards, Lady Bird championed the bill in the press and in private. She sat in on legislative strategy sessions -- a first for a First Lady -- and even called House members personally to ask for their votes. Today, the evidence of her success -- the Highway Beautification Act -- blossoms along roadsides from coast to coast.

Later, Mrs. Johnson lobbied for highways in every state to be seeded with native plants. "I want Texas to look like Texas, and Vermont to look like Vermont, and every state to look like itself," she said. She encouraged local authorities to plant wildflowers instead of grass, explaining that flowers would save taxpayers millions of dollars in mowing and upkeep. Today here in Texas, whenever we drive through the vast fields of bluebonnets and Indian Paintbrush, we have Lady Bird Johnson to thank.

Lady Bird's love of the land found a natural outlet in our national parks. She made dozens of visits to the parks, often with Secretary Udall, to increase public awareness of their beauty and importance. Photographs show Lady Bird gazing in wonder at the heights of California's redwoods, and rafting along the Snake River, with Grand Teton's rugged peaks as a backdrop.

In her White House diaries, Mrs. Johnson recalls a trip to Big Bend National Park. She described Big Bend's scenic mountains, tumbleweeds, roadrunners, and "a few struggling bluebonnets." She praised the tasty Odessa Chuck Wagon barbecue -- enhanced, she wrote, "by the unceasing West Texas wind," which "would deposit a little more sand in my plate." (Laughter.)

She recalled her hike on the Lost Mine trail with Secretary Udall, and a raft trip down the Rio Grande with more than 100 reporters, Secret Service agents and staff. That night, the group told stories around a campfire, snuggled in Navajo blankets beneath a full moon. "What a night to remember!" Mrs. Johnson wrote later. "Sheer magic -- and a day worth five ordinary days of living."

Lady Bird Johnson wanted every American to experience the magic of our national parks. She made park preservation a priority of her husband's administration. She championed the National Historic Preservation Act, which President Johnson signed 41 years ago today. The Act launched the first coordinated federal effort to safeguard our country's heritage, and has led to four decades of terrific preservation work throughout the United States. (Applause.)

And, as David told you, in 1967, Lady Bird and Laurance Rockefeller helped secure a Congressional Charter for the National Park Foundation. In the charter, Congress envisioned an organization that would, and I quote, "encourage private gifts for the benefit of the National Park Service, and thereby further the conservation of our natural, scenic, historic, scientific, educational, inspiration and recreational resources for future generations of Americans."

Over the last four decades, the National Park Foundation has lived up to its founding promise. The National Park Foundation has been an outstanding part of Lady Bird Johnson's proud conservation legacy. And today you're building on that with a new project. In 1982, Mrs. Johnson donated money and 60 acres of land to establish the National Wildflower Research Center here in Austin. Now called the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, the Wildflower Center will partner with the National Park Foundation to launch a new pilot beautification project in the former First Lady's honor.

Through the First Bloom program, the Foundation and the National Park Service will join with the Wildflower Center and community groups like the Boys and Girls Clubs to connect young people to our national parks. First Bloom will take children on visits to national parks near their homes, introducing them to plant species native to their area. At three-day workshops, park rangers will educate kids about seed cultivation and garden design, and teach children to identify and remove invasive species. With help from flower experts, children will return native plants to their native homes.

First Bloom will start in five pilot cities, with the goal of spreading across the National Park Service. Of course, the ultimate goal is to give children a sense of pride in our natural resources, and to encourage them to be good stewards of our beautiful country. Thank you to the National Park Foundation -- and to all the First Bloom partners -- for this innovative program.

In May 1965, at the White House Conference on Beautification, Lady Bird posed a question: "Can a great democratic society generate the concerted drive to plan -- and having planned, to execute -- the great projects of beauty?" Lady Bird's life was the answer: We can, and we must.

Thanks to each of the National Park Foundation members -- and to each of you -- for your work to extend Lady Bird Johnson's legacy into the 21st century.

Now I'd like to invite Luci Baines Johnson and her family on stage to accept the Founders Award. (Applause.)

END 7:55 P.M. CDT

![]() Printer-Friendly Version

Printer-Friendly Version

![]() Email This Page

Email This Page