- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Budget Management

- Defense

- Economy

- Education

- Energy

- Environment

- Global Diplomacy

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- International Trade

- Iraq

- Judicial Nominations

- Middle East

- National Security

- Veterans

|

Home >

News & Policies >

December 2002

|

Background Information on Smallpox

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

|

12/4/02

I. Smallpox Overview

The Disease

Smallpox is a serious, contagious, and sometimes fatal infectious disease. There is no specific treatment for smallpox disease, and the only prevention is vaccination. The name smallpox is derived from the Latin word for "spotted" and refers to the raised bumps that appear on the face and body of an infected person.

There are two clinical forms of smallpox. Variola major is the severe and most common form of smallpox, with a more extensive rash and higher fever. There are four types of variola major smallpox: ordinary (the most frequent type, accounting for 90% or more of cases); modified (mild and occurring in previously vaccinated persons); flat; and hemorrhagic (both rare and very severe). Historically, variola major has an overall fatality rate of about 30%; however, flat and hemorrhagic smallpox usually are fatal. Variola minor is a less common presentation of smallpox, and a much less severe disease, with death rates historically of 1% or less.

Smallpox outbreaks have occurred from time to time for thousands of years, but the disease is now eradicated after a successful worldwide vaccination program. The last case of smallpox in the United States was in 1949. The last naturally occurring case in the world was in Somalia in 1977. After the disease was eliminated from the world, routine vaccination against smallpox among the general public was stopped because it was no longer necessary for prevention.

Where Smallpox Comes From

Smallpox is caused by the variola virus that emerged in human populations thousands of years ago. Except for laboratory stockpiles, the variola virus has been eliminated. However, in the aftermath of the events of September and October, 2001, there is heightened concern that the variola virus might be used as an agent of bioterrorism. For this reason, the U.S. government is taking precautions for dealing with a smallpox outbreak.

Transmission

Generally, direct and fairly prolonged face-to-face contact is required to spread smallpox from one person to another. Smallpox also can be spread through direct contact with infected bodily fluids or contaminated objects such as bedding or clothing. Rarely, smallpox has been spread by virus carried in the air in enclosed settings such as buildings, buses, and trains. Humans are the only natural hosts of variola. Smallpox is not known to be transmitted by insects or animals.

A person with smallpox is sometimes contagious with onset of fever (prodome phase), but the person becomes most contagious with the onset of rash. At this stage the infected person is usually very sick and not able to move around in the community. The infected person is contagious until the last smallpox scab falls off.

|

Smallpox Disease |

|

|

Incubation Period (Duration: 7 to 17 days) Not contagious |

Exposure to the virus is followed by an incubation period during which people do not have any symptoms and may feel fine. This incubation period averages about 12 to 14 days but can range from 7 to 17 days. During this time, people are not contagious. |

|

Initial Symptoms (Prodrome) (Duration: 2 to 4 days) Sometimes contagious* |

The first symptoms of smallpox include fever, malaise, head and body aches, and sometimes vomiting. The fever is usually high, in the range of 101 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit. At this time, people are usually too sick to carry on their normal activities. This is called the prodrome phase and may last for 2 to 4 days. |

|

Early Rash (Duration: about 4 days) Most contagious

Rash distribution:

|

A rash emerges first as small red spots on the tongue and in the mouth. These spots develop into sores that break open and spread large amounts of the virus into the mouth and throat. At this time, the person becomes contagious. Around the time the sores in the mouth break down, a rash appears on the skin, starting on the face and spreading to the arms and legs and then to the hands and feet. Usually the rash spreads to all parts of the body within 24 hours. As the rash appears, the fever usually falls and the person may start to feel better. By the third day of the rash, the rash becomes raised bumps. By the fourth day, the bumps fill with a thick, opaque fluid and often have a depression in the center that looks like a bellybutton. (This is a major distinguishing characteristic of smallpox.) Fever often will rise again at this time and remain high until scabs form over the bumps. |

|

Pustular Rash (Duration: about 5 days) Contagious |

The bumps become pustules—sharply raised, usually round and firm to the touch as if there’s a small round object under the skin. People often say the bumps feel like BB pellets embedded in the skin. |

|

Pustules and Scabs (Duration: about 5 days) Contagious |

The pustules begin to form a crust and then scab. By the end of the second week after the rash appears, most of the sores have scabbed over. |

|

Resolving Scabs (Duration: about 6 days) Contagious |

The scabs begin to fall off, leaving marks on the skin that eventually become pitted scars. Most scabs will have fallen off three weeks after the rash appears. The person is contagious to others until all of the scabs have fallen off. |

|

Scabs resolved Not contagious |

Scabs have fallen off. Person is no longer contagious. |

*Smallpox may be contagious during the prodrome phase, but is most infectious during the first 7 to 10 days following rash onset.

II. Vaccine Overview

The Smallpox Vaccine

The smallpox vaccine helps the body develop immunity to smallpox. The vaccine is made from a virus called vaccinia which is a "pox"-type virus related to smallpox. The smallpox vaccine contains the "live" vaccinia virus—not dead virus like many other vaccines. For that reason, the vaccination site must be cared for carefully to prevent the virus from spreading. Also, the vaccine can have side effects (see the section "Smallpox Vaccine Safety" in this fact sheet). The vaccine does not contain the smallpox virus and cannot give you smallpox.

Currently, the United States has a big enough stockpile of smallpox vaccine to vaccinate everyone who might need it in the event of an emergency. Production of new vaccine is underway.

Length of Protection

Smallpox vaccination provides full immunity for 3 to 5 years and decreasing immunity thereafter. If a person is vaccinated again later, immunity lasts even longer. Historically, the vaccine has been effective in preventing smallpox infection in 95% of those vaccinated. In addition, the vaccine was proven to prevent or substantially lessen infection when given within a few days of exposure. It is important to note, however, that at the time when the smallpox vaccine was used to eradicate the disease, testing was not as advanced or precise as it is today, so there may still be things to learn about the vaccine and its effectiveness and length of protection.

Receiving the Vaccine

The smallpox vaccine is not given with a hypodermic needle. It is not a shot as most people have experienced. The vaccine is given using a bifurcated (two-pronged) needle that is dipped into the vaccine solution. When removed, the needle retains a droplet of the vaccine. The needle is used to prick the skin 15 times in a few seconds. The pricking is not deep, but it will cause a sore spot and one or two droplets of blood to form. The vaccine usually is given in the upper arm.

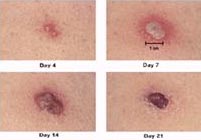

If the vaccination is successful, a red and itchy bump develops at the vaccine site in three or four days. In the first week, the bump becomes a large blister, fills with pus, and begins to drain. During the second week, the blister begins to dry up and a scab forms. The scab falls off in the third week, leaving a small scar. People who are being vaccinated for the first time have a stronger reaction than those who are being revaccinated. The following pictures show the progression of the site where the vaccine is given.

Smallpox vaccination site

Days 4 through 21

Post-Vaccination Care

After vaccination, it is important to follow care instructions for the site of the vaccine. Because the virus is live, it can spread to other parts of the body, or to other people. The vaccinia virus (the live virus in the smallpox vaccine) may cause rash, fever, and head and body aches. In certain groups of people (see the section "Smallpox Vaccine Safety" in this fact sheet), complications from the vaccinia virus can be severe.

Benefit of Vaccine Following Exposure

Vaccination within 3 days of exposure will prevent or significantly lessen the severity of smallpox symptoms in the vast majority of people. Vaccination 4 to 7 days after exposure likely offers some protection from disease or may modify the severity of disease.

Smallpox Vaccine Safety

The smallpox vaccine is the best protection you can get if you are exposed to the smallpox virus. Anyone directly exposed to smallpox, regardless of health status, would be offered the smallpox vaccine because the risks associated with smallpox disease are far greater than those posed by the vaccine.

There are side effects and risks associated with the smallpox vaccine. Most people experience normal, usually mild reactions that include a sore arm, fever, and body aches. However, other people experience reactions ranging from serious to life-threatening. People most likely to have serious side effects are: people who have had, even once, skin conditions (especially eczema or atopic dermatitis) and people with weakened immune systems, such as those who have received a transplant, are HIV positive, are receiving treatment for cancer, or are currently taking medications (like steroids) that suppress the immune system. In addition, pregnant women should not get the vaccine because of the risk it poses to the fetus. And people under 18 years of age and those allergic to the vaccine or any of its components should not receive the vaccine.

In the past, about 1,000 people for every 1 million people vaccinated for the first time experienced reactions that, while not life-threatening, were serious. These reactions included a toxic or allergic reaction at the site of the vaccination (erythema multiforme), spread of the vaccinia virus to other parts of the body and to other individuals (inadvertent inoculation), and spread of the vaccinia virus to other parts of the body through the blood (generalized vaccinia). These types of reactions may require medical attention. In the past, between 14 and 52 people out of every 1 million people vaccinated for the first time experienced potentially life-threatening reactions to the vaccine. Based on past experience, it is estimated that 1 or 2 people in 1 million who receive the vaccine may die as a result. Careful screening of potential vaccine recipients is essential to ensure that those at increased risk do not receive the vaccine.

Smallpox Vaccine Availability

Routine smallpox vaccination among the American public stopped in 1972 after the disease was eradicated in the United States. Until recently, the U.S. government provided the vaccine only to a few hundred scientists and medical professionals working with smallpox and similar viruses in a research setting.

After the events of September and October, 2001, however, the U.S. government took further actions to improve its level of preparedness against terrorism. One of many such measures—designed specifically to prepare for an intentional release of the smallpox virus—included updating and releasing a smallpox response plan. In addition, the U.S. government ordered production of enough smallpox vaccine to immunize the American public in the event of a smallpox outbreak. Right now, the U.S. government has access to enough smallpox vaccine to effectively respond to a smallpox outbreak in the United States.

III.

People Who Should NOT Get the Smallpox Vaccine(Unless they are Exposed to the Smallpox Virus)

Some people are at greater risk for serious side effects from the smallpox vaccine. Individuals who have any of the following conditions, or live with someone who does, should NOT get the smallpox vaccine unless they have been exposed to the smallpox virus.

- Eczema or atopic dermatitis. (This is true even if the condition is not currently active, mild or experienced as a child.)

- Skin conditions such as burns, chickenpox, shingles, impetigo, herpes, severe acne, or psoriasis. (People with any of these conditions should not get the vaccine until they have completely healed.)

- Weakened immune system. (Cancer treatment, an organ transplant, HIV, or medications to treat autoimmune disorders and other illnesses can weaken the immune system.)

- Pregnancy or plans to become pregnant within one month of vaccination.

In addition, individuals should not get the smallpox vaccine if they:

- Are allergic to the vaccine or any of its ingredients.

- Are younger than 12 months of age. However, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) advises against non-emergency use of smallpox vaccine in children younger than 18 years of age.

- Have a moderate or severe short-term illness. (These people should wait until they are completely recovered to get the vaccine.)

- Are currently breastfeeding.

Again, people who have been directly exposed to the smallpox virus should get the vaccine, regardless of their health status.

Don’t Hesitate!

If offered the smallpox vaccine, individuals should tell their immunization provider if they have any of the above conditions, or even if they suspect they might.

IV. Reactions after Smallpox Vaccination

The smallpox vaccine prevents smallpox. For most people, it is safe and effective. Most people experience normal, typically mild reactions to the vaccine, which indicate that it is beginning to work. Some people may experience reactions that may require medical attention.

Normal, Typically Mild Reactions

These reactions usually go away without treatment:

- The arm receiving the vaccination may be sore and red where the vaccine was given.

- The glands in the armpits may become large and sore.

- The vaccinated person may run a low fever.

- One out of 3 people may feel bad enough to miss work, school, or recreational activity or have trouble sleeping.

Serious Reactions

In the past, about 1,000 people for every 1 million people vaccinated for the first time experienced reactions that, while not life-threatening, were serious. These reactions may require medical attention:

- A vaccinia rash or outbreak of sores limited to one area. This is an accidental spreading of the vaccinia virus caused by touching the vaccination site and then touching another part of the body or another person. It usually occurs on the genitals or face, including the eyes, where it can damage sight or lead to blindness. Washing hands with soap and water after touching the vaccine site will help prevent this (inadvertent inoculation).

- A widespread vaccinia rash. The virus spreads from the vaccination site through the blood. Sores break out on parts of the body away from the vaccination site (generalized vaccinia).

- A toxic or allergic rash in response to the vaccine that can take various forms (erythema multiforme).

Life-Threatening Reactions

Rarely, people have had very bad reactions to the vaccine. In the past, between 14 and 52 people per 1 million people vaccinated for the first time experienced potentially life-threatening reactions. These reactions require immediate medical attention:

- Eczema vaccinatum. Serious skin rashes caused by widespread infection of the skin in people with skin conditions such as eczema or atopic dermatitis.

- Progressive vaccinia (or vaccinia necrosum). Ongoing infection of skin with tissue destruction frequently leading to death.

- Postvaccinal encephalitis. Inflammation of the brain.

People with certain medical conditions—including people with weakened immune systems or certain skin conditions—are more likely to have these reactions and should not get the smallpox vaccine unless they have been exposed to smallpox.

Based on past experience, it is estimated that between 1 and 2 people out of every 1 million people vaccinated may die as a result of life-threatening reactions to the vaccine.

Important Note: Statistical information about smallpox vaccine adverse reactions is based on data from two studies conducted in 1968. Adverse event rates in the United States today may be higher because there may be more people at risk from immune suppression (from cancer, cancer therapy, organ transplants, and illnesses such as HIV/AIDS) and eczema or atopic dermatitis. The outcome associated with adverse events may be less severe than previously reported because of advances in medical care. Rates may be lower for persons previously vaccinated.

V. Smallpox Vaccine: Adverse Event Rates, 1968

(number per million vaccinees)

|

NATIONAL SURVEY |

TEN STATE SURVEY |

|||

|

All primary (i.e. first-time) |

Vaccinees |

All primary (i.e. first-time) |

Vaccinees |

|

|

Serious, but not life-threatening reactions: |

||||

|

Inadvertent Inoculation |

25.4 |

27.1 |

529.2 |

532.0 |

|

Generalized Vaccinia |

23.4 |

17.7 |

241.5 |

222.8 |

|

Erythema Multiforme |

Not Available |

Not |

164.6 |

131.3 |

Total number of serious, but not life-threatening reactions: |

48.8 |

|

935.3* |

|

|

Life-threatening reactions: |

||||

|

Postvaccinal Encephalitis |

2.9 |

2.4 |

12.3 |

8.6 |

Progressive Vaccinia (Vaccinia Necrosum) |

.9 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

|

Eczema Vaccinatum |

10.4 |

10.6 |

38.5 |

41.5 |

Total number of life-threatening reactions: |

14.2* |

|

52.3* |

|

|

Deaths: |

1.1* |

.6 |

None Reported |

None Reported |

*Note: Adverse event statistics cited in document are marked with an asterisk and highlighted.

The table above presents smallpox vaccine adverse event rates from two studies done in 1968 (see references below). The two studies were carried out using different methodologies. In the national survey, information was gathered from seven nationwide sources, with most of the information on adverse reactions coming from the American Red Cross Vaccinia Immune Globulin (VIG) distribution system. Reactions that did not require use of VIG (that is, less severe reactions) are less likely to be reported through this system. In the ten state survey on the other hand, doctors were directly surveyed to report all adverse reactions, even those considered less severe. For this reason, the ten-state survey data may present a better estimate of the number of people having adverse reactions to the vaccine.

Adverse event rates in the United States today may be higher because there may be more people at risk from 1) immune suppression from cancer, cancer therapy, organ transplantation and other illnesses, such as HIV/AIDS, and 2) eczema or atopic dermatitis. The outcome associated with adverse events may be less severe than previously reported because of advances in medical care. Rates may be lower for persons previously vaccinated.

IN DEPTH:

The National Survey

In this study, patients with suspected complications of smallpox vaccination in 1968 were detected through seven nationwide sources, including the American Red Cross Vaccinia Immune Globulin (VIG) distribution system, state and territorial epidemiologists, pharmaceutical companies producing smallpox vaccine and products used to treat adverse reactions, and the CDC’s disease surveillance systems.

The authors identified 572 persons in the U.S. who had confirmed vaccination complications in 1968. Patients receiving VIG from the American Red Cross during 1968 represented the majority (82.5%) of the cases in this study. 68% of the patients were primary vaccinees, 7% were revaccinees, 20% acquired vaccinia through contact with a vaccinee (e.g., a playmate or sibling), and 5% had unknown histories of vaccination. The total number of persons who received smallpox vaccinations in 1968 was determined using CDC’s United States Immunization Survey. The estimated total number of vaccinations given during that year was 14,168,000. The incidence rates for adverse events per 1 million vaccinated persons are presented in the table above.

The Ten-State Survey

In this study, practicing physicians in ten states (AL, AK, IA, KY, ME, MD, RI, SC, WA, WV) were surveyed to obtain information about whether they had seen any patients with smallpox vaccination complications in 1968, the types of complications seen, and the age, sex, date of vaccination, vaccination history, and date of onset of complications of each patient. Clinical descriptions of patients were also elicited, and were supplemented by chart reviews of hospitalized patients. The average physician response rate for 8 out of the 10 states was 83.9%. Two of the states had response rates of 49% and 44%.

968 patients who experienced vaccination complications were detected. 84% of the patients were primary vaccinees, 11% were revaccinees, and 5% were contacts of vaccinees; only 6.6% of the patients had received VIG. The total number of persons who received smallpox vaccinations in each of the ten states in 1968 was determined using CDC’s National Immunization Survey. The estimated total number of vaccinations given in the participating states during that year was 1,648,000. The incidence rates for adverse events per 1 million vaccinated persons are presented in the table above.

Differences in Adverse Event Rates

The adverse event rates per million vaccinations are considerably higher in the ten-state study, particularly those for the less severe complications (generalized vaccinia and accidental autoinoculation). The authors of the studies assert that previous research demonstrates that direct survey techniques, such as those used in the ten-state survey, uncover at least 10 times as many cases of generalized vaccinia, accidental inoculation and mild eczema vaccinatum as the VIG distribution system detects. The VIG distribution system also fails to detect many patients with vaccinial encephalitis, because the condition is not treatable with VIG. Most of the life-threatening complications occurring in the ten states, on the other hand, were detected by the national surveillance program.

The authors of the studies state that the national survey statistics should be considered minimal estimates of the risks of smallpox vaccination. The authors assert, on the other hand, that a small number of patients included in the ten-state survey may have been vaccinated prior to or after 1968. Those rates, therefore, may overestimate slightly the true incidence of complications. Thus, when describing rates of the more severe smallpox vaccine adverse events in 1968 (vaccinial encephalitis, vaccinia necrosum, and eczema vaccinatum), it appears to be preferable to use the range presented by the two studies. The ten-state survey data may present a better estimate of less severe adverse event rates from 1968 (generalized vaccinia and accidental autoinoculation).

- Lane JM, Ruben FL, Neff JM, Millar JD. Complications of smallpox vaccinations, 1968: national surveillance in the United States. New Engl J Med 1969;281:1201-1208.

- Lane JM, Ruben FL, Neff JM, Millar JD. Complications of smallpox vaccination, 1968: results of ten statewide surveys. J Infect Dis 1970;122:303-309.